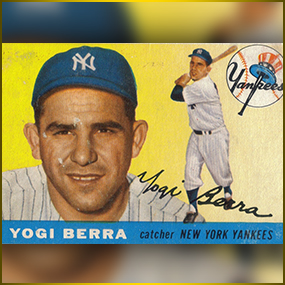

Yankee Catcher Was Known More For His Wit and Wisdom Than For His Amazing Career!

Yogi Berra, one of the greatest catchers in Major League Baseball history, who who as a player was a mainstay of 10 Yankees championship teams and as a manager led both the Yankees and the Mets to the World Series passed away at the age of 90 years old on Tuesday … but the legendary Hall of Famer will no doubt be better known for his witty sayings (“It ain’t over ’til it’s over!”) than for being one of the most successful baseball players of all time.

His death was announced by the Yankees and the Yogi Berra Museum and Learning Center in Little Falls, New Jersey. His sayings, of course, will go down in history.

“You can observe a lot just by watching.”

“When you come to a fork in the road, take it.”

“Nobody goes there anymore … it’s too crowded!”

According to his obituary which was just posted on The New York Times website and will run in tomorrow’s print newspaper, The character Yogi Berra may even have overshadowed the Hall of Fame ballplayer Yogi Berra, obscuring what a remarkable athlete he was. A notorious bad-ball hitter — he swung at a lot of pitches that were not strikes but mashed them anyway — he was fearsome in the clutch and the most durable and consistently productive Yankee during the period of the team’s most relentless success.

In addition, as a catcher, he played the most grueling position on the field. (For a respite from the chores and challenges of crouching behind the plate, Berra, who played before the designated hitter rule took effect in the American League in 1973, occasionally played the outfield.)

Casey Stengel, a Hall of Fame manager whose shrewdness and talent were also often underestimated, recognized Berra’s gifts. He referred to Berra, even as a young player, as his assistant manager and compared him favorably to star catchers of previous eras like Mickey Cochrane, Gabby Hartnett and Bill Dickey. “You could look it up” was Stengel’s catchphrase, and indeed the record book declares that Berra was among the greatest catchers in the history of the game — some say the greatest of all.

Berra’s career batting average, .285, was not as high as that of his Yankees predecessor, Dickey (.313), but Berra hit more home runs (358 in all) and drove in more runs (1,430). Praised by pitchers for his astute pitch-calling, Berra led the American League in assists five times and from 1957 through 1959 went 148 consecutive games behind the plate without making an error, a major league record at the time.

He was not a defensive wizard from the start, though. Dickey, Berra explained, “learned me all his experience.”

On defense, he certainly surpassed Mike Piazza, the best-hitting catcher of recent vintage, and maybe ever. On offense, Berra and Johnny Bench, whose Cincinnati Reds teams of the 1970s were known as the Big Red Machine, were comparable, except that Bench struck out three times as often. Berra whiffed a mere 414 times in more than 8,300 plate appearances over 19 seasons — an astonishingly small ratio for a power hitter.

Others — Carlton Fisk, Gary Carter and Ivan Rodriguez among them — also deserve consideration in a discussion of great catchers, but none was clearly superior to Berra on offense or defense. Only Roy Campanella, a contemporary rival who played for the Brooklyn Dodgers and faced Berra in the World Series six times before his career was ended by a car accident, equaled Berra’s total of three Most Valuable Player Awards. And although Berra did not win the award in 1950 — his teammate Phil Rizzuto did — he gave one of the greatest season-long performances by a catcher that year, hitting .322, smacking 28 home runs and driving in 124 runs.

Beyond the historic moments and individual accomplishments, what most distinguished Berra’s career was how often he won. From 1946 to 1985, as a player, coach and manager, Berra appeared in a remarkable 21 World Series. Playing on powerful Yankees teams with teammates like Rizzuto and Joe DiMaggio early on and then Whitey Ford and Mickey Mantle, Berra starred on World Series winners in 1947, ’49, ’50, ’51, ’52, ’53, ’56 and ’58. He was a backup catcher and part-time outfielder on the championship teams of 1961 and ’62. (He also played on World Series losers in 1955, ’57, ’60 and ’63.)

All told, his Yankees teams won the American League pennant 14 out of 17 years. He still holds Series records for games played, plate appearances, hits and doubles.

No other player has been a champion so often.

Lawrence Peter Berra was born on May 12, 1925, in the Italian enclave of St. Louis known as the Hill, which also fostered the baseball career of his boyhood friend Joe Garagiola. Berra was the fourth of five children. His father, Pietro, a construction worker and bricklayer, and his mother, Paulina, were immigrants from Malvaglio, a northern Italian village near Milan. (As an adult, on a visit to his ancestral home, Berra took in a performance of “Tosca” at La Scala. “It was pretty good,” he said. “Even the music was nice.”)

As a boy, Berra was known as Larry, or Lawdie, as his mother pronounced it. As recounted in “Yogi Berra: Eternal Yankee,” a 2009 biography by Allen Barra, one day in his early teens, young Larry and some friends went to the movies and were watching a travelogue about India when a Hindu yogi appeared on the screen sitting cross-legged. His posture struck one of the friends as precisely the way Berra sat on the ground as he waited his turn at bat. From that day on, he was Yogi Berra.

An ardent athlete but an indifferent student, Berra dropped out of school after the eighth grade. He played American Legion ball and worked odd jobs. As teenagers, he and Garagiola tried out with the St. Louis Cardinals and were offered contracts by the Cardinals’ general manager, Branch Rickey. But Garagiola’s came with a $500 signing bonus and Berra’s just $250, so Berra declined to sign. (This was a harbinger of deals to come. Berra, whose salary as a player reached $65,000 in 1961, substantial for that era, proved to be a canny contract negotiator, almost always extracting concessions from the Yankees’ penurious general manager, George Weiss.)

In the meantime, the St. Louis Browns — they later moved to Baltimore and became the Orioles — also wanted to sign Berra but were not willing to pay any bonus at all. Then, the day after the 1942 World Series, in which the Cardinals beat the Yankees, a Yankees coach showed up at Berra’s parents’ house and offered him a minor league contract — along with the elusive $500.

As a Yankee, Berra became a fan favorite, partly because of his superior play — he batted .305 and drove in 98 runs in 1948, his second full season — and partly because of his humility and guilelessness. In 1947, honored at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, a nervous Berra told the hometown crowd, “I want to thank everyone for making this night necessary.”

Berra was a hit with sportswriters, too, although they often portrayed him as a baseball idiot savant, an apelike, barely literate devotee of comic books and movies who spoke fractured English. So was born the Yogi caricature, of the triumphant rube.

“Even today,” Life magazine wrote in July 1949, “he has only pity for people who clutter their brains with such unnecessary and frivolous matters as literature and the sciences, not to mention grammar and orthography.”

Collier’s magazine declared, “With a body that only an anthropologist could love, the 185-pound Berra could pass easily as a member of the Neanderthal A.C.”

Berra tended to take the gibes in stride. If he was ugly, he was said to have remarked, it did not matter at the plate. “I never saw nobody hit one with his face,” he was quoted as saying. But when writers chided him about his girlfriend, Carmen Short, saying he was too unattractive to marry her, he responded, according to Colliers, “I’m human, ain’t I?”

Berra outlasted the ridicule. He married Short in 1949, and the marriage endured until her death in 2014. He is survived by their three sons — Tim, who played professional football for the Baltimore Colts; Dale, a former infielder for the Yankees, the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Houston Astros; and Lawrence Jr. — as well as 11 grandchildren and a great-grandson.

Certainly, assessments of Berra changed over the years.

“He has continued to allow people to regard him as an amiable clown because it brings him quick acceptance, despite ample proof, on field and off, that he is intelligent, shrewd and opportunistic,” Robert Lipsyte wrote in The New York Times in October 1963.

At the time, Berra had just concluded his career as a Yankees player, and the team had named him manager, a role in which he continued to find success, although not with the same regularity he enjoyed as a player and not without drama and disappointment. Indeed, things began badly. The Yankees, an aging team in 1964, played listless ball through much of the summer, and in mid-August they lost four straight games in Chicago to the first-place White Sox, leading to one of the kookier episodes of Berra’s career.

On the team bus to O’Hare Airport, the reserve infielder Phil Linz began playing “Mary Had a Little Lamb” on the harmonica. Berra, in a foul mood over the losing streak, told him to knock it off, but Linz did not. (In another version of the story, Linz asked Mickey Mantle what Berra had said, and Mantle responded, “He said, ‘Play it louder.’ ”) Suddenly the harmonica went flying, having been either knocked out of Linz’s hands by Berra or thrown at Berra by Linz. (Players on the bus had different recollections.)

News reports of the incident made it sound as if Berra had lost control of the team, and although the Yankees caught and passed the White Sox in September, winning the pennant, Ralph Houk, the general manager, fired Berra after the team lost a seven-game World Series to St. Louis. In a bizarre move, Houk replaced him with the Cardinals’ manager, Johnny Keane.

Keane’s Yankees finished sixth in 1965.

Berra, meanwhile, moved across town, taking a job as a coach for the famously awful Mets under Stengel, who was finishing his career in Flushing. The team continued its mythic floundering until 1969, when the so-called Miracle Mets, with Gil Hodges as manager — and Berra coaching first base — won the World Series.

After Hodges died, before the start of the 1972 season, Berra replaced him. That summer, Berra was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

The Mets team he inherited, however, faltered, finishing third, and for most of the 1973 season they were worse. In mid-August, the Mets were well under .500 and in sixth place when Berra supposedly uttered perhaps the most famous Yogi-ism of all.

“It ain’t over till it’s over,” he said (or words to that effect), and lo and behold, the Mets got hot, squeaking by the Cardinals to win the National League’s Eastern Division title.

They then beat the Reds in the League Championship Series before losing to the Oakland Athletics in the World Series. Berra was rewarded for the resurgence with a three-year contract, but the Mets were dreadful in 1974, finishing fifth, and the next year, on Aug. 6, with the team in third place and having lost five straight games, Berra was fired.

Once again he switched leagues and city boroughs, returning to the Bronx as a Yankees coach, and in 1984 the owner, George Steinbrenner, named him to replace the volatile Billy Martin as manager. The team finished third that year, but during spring training in 1985, Steinbrenner promised him that he would finish the season as Yankees manager no matter what

After just 16 games, however, the Yankees were 6-10, and the impatient and imperious Steinbrenner fired Berra anyway, bringing back Martin. Perhaps worse than breaking his word, Steinbrenner sent an underling to deliver the bad news.

The firing, which had an added sting because Berra’s son Dale had recently joined the Yankees, provoked one of baseball’s legendary feuds, and for 14 years Berra refused to set foot in Yankee Stadium, a period during which he coached four seasons for the Houston Astros.

In the meantime private donors helped establish the Yogi Berra Museum and Learning Center on the New Jersey campus of Montclair State University, which awarded Berra an honorary doctorate of humanities in 1996. A minor league ballpark, Yogi Berra Stadium, opened there in 1998.

The museum, a tribute to Berra with exhibits on his career, runs programs for children dealing with baseball history. In January 1999, Steinbrenner, who died in 2010, went there to make amends.

“I know I made a mistake by not letting you go personally,” he told Berra. “It’s the worst mistake I ever made in baseball.”

Berra chose not to quibble with the semi-apology. To welcome him back into the Yankees fold, the team held a Yogi Berra Day on July 18, 1999. Also invited was Larsen, who threw out the ceremonial first pitch, which Berra caught.

Incredibly, in the game that day, David Cone of the Yankees pitched a perfect game.

It was, as Berra may or may not have said in another context, “déjà vu all over again,” a fittingly climactic episode for a wondrous baseball life.

Of course, we’re HustleTweeting about Yogi Berra, and you’re more than welcome to join the conversation by following the Hustle on Twitter HERE or write to us directly at hustleoncrave@gmail.com Hey, have you checked out the Hustle’s Ultra High Quality You Tube Channel, with exclusive videos featuring the #HUSTLEBOOTYTEMPTATS SUPERMODEL OF THE YEAR … OUR WORLD EXCLUSIVE WITH MIKE TYSON … BROCK LESNAR’S “HERE COMES THE PAIN” … ICE-T AND COCO’s SEX SECRETS … MMA BAD BOY NICK DIAZ … the list goes on and on, so if you’re not subscribing, you’re missing something … and by the ways cheapos, it’s FREE! Yes, absolutely 100 percent FREE! What are you waiting for? Check it out HERE

By the way, we’re also old school social networkers, so check out our interactive skills on Facebook HERE and even on MySpace HERE. If you’re on Friendster, GFY … and have a pleasant tomorrow!

![]()

WE HERE AT THE HEYMAN HUSTLE HAVE ENSLAVED HIGHLY TRAINED

MONKEYS TO IGNORE THE FACT THEY ARE OVERWORKED AND UNDERPAID,

ALL IN THE NAME OF SCOURING THE WORLD WIDE WEB TO FIND THE FIFTEEN

MOST PROVOCATIVE STORIES ON THE INTERNET. ALL FOR YOU. NO ONE ELSE

BUT YOU. JUST YOU. AND ALL YOU NEED TO DO IS PICK WHICH PIC TO CLICK!