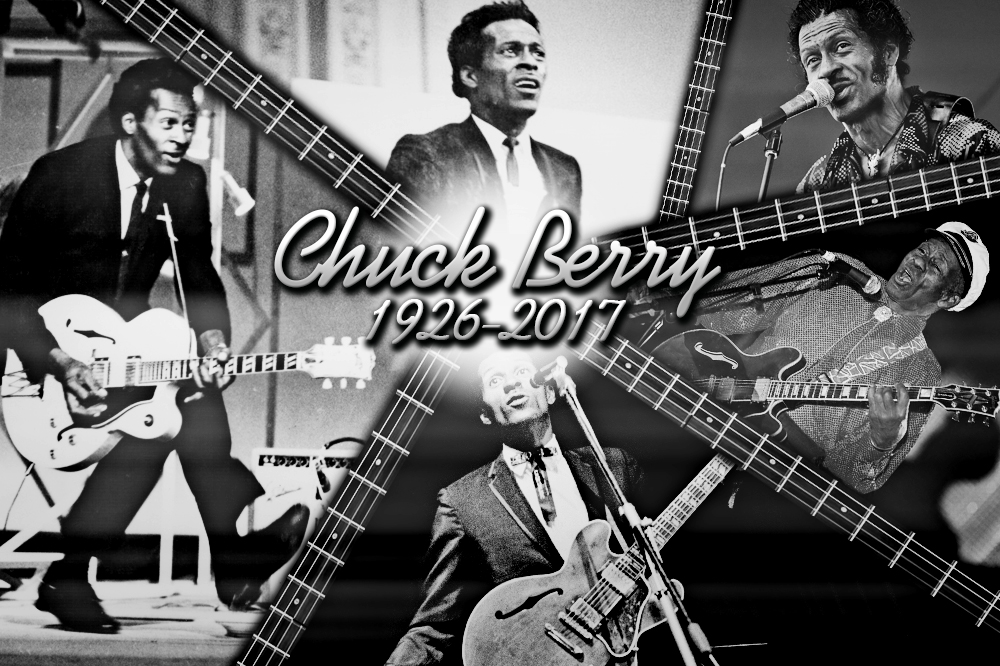

Chuck Berry passed away a few hours ago, March 18th, at his home in St. Charles County, Mo. He was 90 years old.

In 1986, when The Rock n Roll Hall of Fame inducted him, his induction read “While no individual can be said to have invented rock and roll, Chuck Berry comes the closest of any single figure to being the one who put all the essential pieces together.”

A seminal figure in early rock music, he was all the rarer still for writing, singing and playing his own music. His songs and the boisterous performance standards he set directly influenced the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and later Bruce Springsteen and Bob Seger. Not to mention he is the inspiration for perhaps this generation’s greatest guitar player, Angus Young.

John Lennon once said, “If you tried to give rock-and-roll another name, you might call it Chuck Berry!”

But his amazing talent was almost overshadowed several time by his tumultuous life.

He was 30, married and the father of two when he made his first recording, “Maybellene” in 1955. The song — a story of a man in a Ford V8 chasing his unfaithful girlfriend in a Cadillac Coupe de Ville — charted No. 1 on Billboard’s rhythm-and-blues chart and No. 5 on the pop music charts.

It was soon followed by “Rock and Roll Music” and “Sweet Little Sixteen,” whose astute reference to the teen-oriented TV show “American Bandstand” (“Well, they’ll be rockin’ on Bandstand, Philadelphia, P.A.”) helped him connect to adolescent record-buyers.

When he went into his signature “duck walk,” his legs seemed to be made of rubber, and his whole body moved with clocklike precision — the visual statement of his music’s kinetic energy. His charisma was the gold standard for all the rock-and-roll extroverts who followed.

He once claimed that he initiated the duck walk at the Brooklyn Paramount Theater in 1956, based on a pose he sometimes struck as a child. “I had nothing else to do during the instrumental part of the song,” he said. “I did it, and here comes the applause. Well, I knew to coin anything that was that entertaining, so I kept it up.”

He was credited with penning more than 100 songs, the best known of which used carefully crafted rhymes and offered tightly written vignettes about American life. They became an influential part of the national soundtrack for generations of listeners and practitioners.

“Back in the U.S.A.” (1959), later covered by Linda Ronstadt, delighted in an America where “hamburgers sizzle on an open grill night and day.” And “School Day (Ring! Ring! Goes the Bell)” (1957), written about the over-crowded St. Louis schools of his youth, became an anthem for bored, restless kids everywhere.

The Beach Boys had a hit record with “Surfin’ USA” (1963), its melody borrowed without credit from “Sweet Little Sixteen.” The Beatles began their first U.S. concert, at the Washington Coliseum, with their version of Chuck Berry‘s “Roll Over Beethoven” (1956).

Perhaps the most famous and also the most performed of his songs — indeed, one of the most performed of all rock songs — was “Johnny B. Goode” (1957). Its storyline embodied Chuck Berry‘s own experience as a black man born into segregation who lived to see “his name in lights:”

Deep down Louisiana close to New Orleans

Way back up in the woods among the evergreens

There stood a log cabin made of earth and wood

Where lived a country boy named Johnny B. Goode

Who never ever learned to read or write so well

But he could play the guitar just like a ringin’ a bell

In his 1987 memoir, he said, “The gateway from freedom, I was told, was somewhere near New Orleans where most Africans were sorted through and sold (into slavery). I’d been told my grandfather lived back up in the woods among the evergreens in a log cabin. I revived the era with a story about a colored boy named Johnny B. Goode.”

But Chuck Berry wanted the song to have a wider appeal. “I thought it would seem biased to my white fans to say ‘olored boy so I changed it to country boy.”

Charles Edward Anderson Berry was born in St. Louis on October 18, 1926. His father was a carpenter and handyman. Chuck was 14 when he began playing guitar and performing at parties, but that was interrupted by a three-year stint in reform school for his role in a bungled armed robbery. After his release, he worked on an automobile assembly line while studying for a career in hairdressing.

On weekends, he sang at the Cosmopolitan Club in East St. Louis, Illinois, with a group led by pianist Johnnie Johnson, who later played (magnificently, we might add) on many of Chuck’s records.

At the urging of Muddy Waters, Chuck took his demo tapes to Chess Records, the Chicago label that specialized in blues and urban rhythm-and-blues. Label owner Leonard Chess was impressed by “Ida May,” a country-and-western-styled tune, and said he would allow Chuck to record it if he would change the name to “Maybellene.”

The song’s countrified style and Chuck’s non-bluesy intonation reportedly led many disc jockeys to assume that he was white, and the song’s popularity with white record-buyers helped spur his quick rise in the music industry.

His savvy about the unsavory business practices of the day — giving co-writing credits to deejays, such as Alan Freed, in exchange for frequent airplay — also propelled his career.

His career was nearly derailed in 1959, when he was arrested on a federal charge of taking a 14-year-old girl across state lines for immoral purposes. Chuck Berry was convicted but granted an appeal on the basis of racist remarks made by the judge. A second trial also ended in a conviction. Chuck eventually served 18 months of a three-year sentence and paid a $10,000 fine.

He was released in 1963, soon to find his career overtaken by a second wave of rockers and the so-called British invasion of bands, such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. He continued to be drawn into the headlines by legal troubles. In 1979, he served four months in Lompoc Federal Prison in California for tax evasion.

In 1989, Hosana Huck, a cook in Chuck’s St. Louis restaurant, the Southern Air, sued him, claiming that he secretly videotaped her and other women in the establishment’s restroom. Huck’s suit was followed by a class-action suit by other unnamed women. Chuck denied any wrongdoing but settled out of court in 1995 for $1.5 million.

So what was his biggest hit?

Well, in 1972, Chuck had the biggest hit of his career with “My Ding-a-Ling,” a double-entendre novelty song that was included on the album “The London Chuck Berry Sessions” (even though he recorded the song not in London but at a concert in Coventry, England). The New Orleans songwriter Dave Bartholomew wrote and recorded it in 1952; Chuck recorded a similar song, “My Tambourine,” in 1968, and is credited on recordings as the sole songwriter of the 1972 “My Ding-a-Ling.” It turned out to be his only #1 pop single.

We present “Mean Old World” from a live special from London that year. If you watch about five minutes into the song, Chuck starts playing the guitar, as if he’s in a trance, like a violin.

Effortlessly.

Cuz he was Chuck Berry.

And there was no one like him.

He was rock n roll!

We’re HustleTweeting about Chuck Berry, and you’re more than welcome to join the conversation by following the Hustle Twitter HERE and also liking our hyper-interactive Facebook page HERE!